Mysterious Structures Balloon From Milky Way's Core

Published November 10, 2010

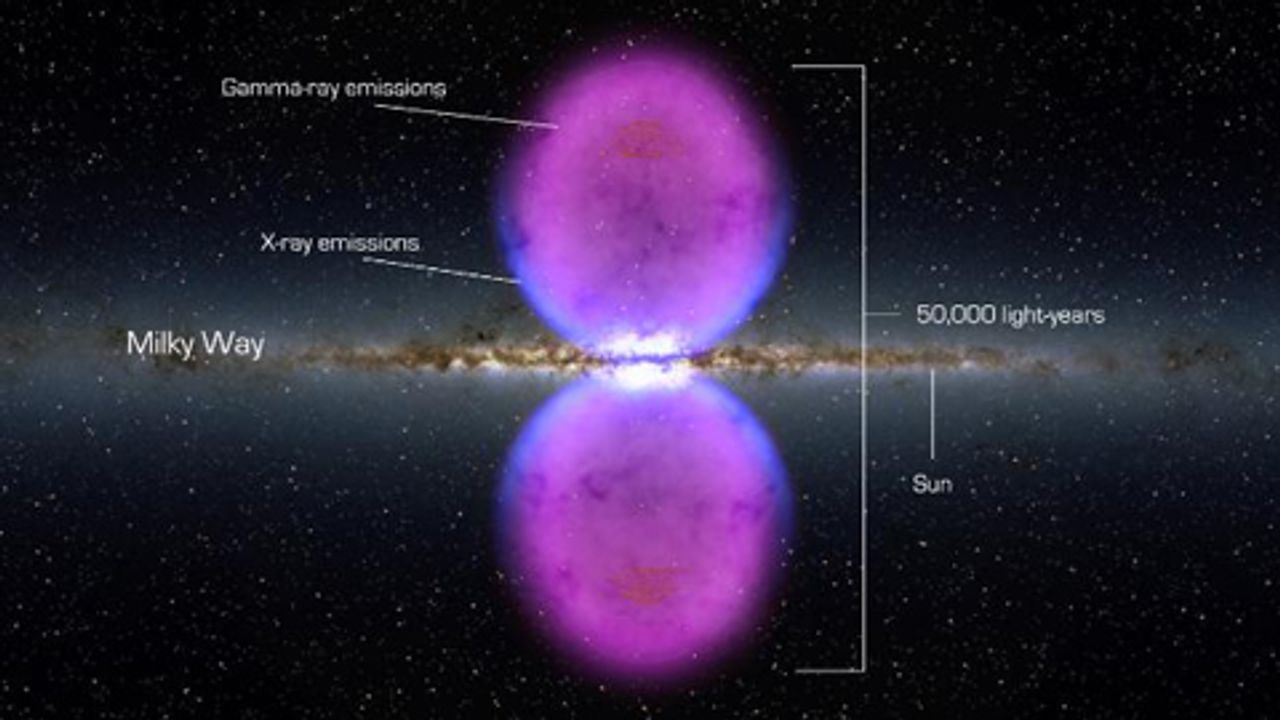

Two huge bubbles that emit gamma rays have been found billowing from the center of the Milky Way galaxy, astronomers have announced.

The previously unseen structures, detected by NASA's Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope, extend 25,000 light-years north and south from the galactic core.

"We think we know a lot about our own galaxy," Princeton University astrophysicist David Spergel, who was not involved in the discovery, said during a press briefing Tuesday. But "what we see here are these enormous structures … [that] suggest the presence of an enormous energetic event in the center of our galaxy."

For now the source of all that energy is unclear, said study co-author Doug Finkbeiner, an associate professor of astronomy at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Gamma rays are the most energetic forms of light, and in space they tend to come from violent events such as supernovae or from extreme objects such as black holes and neutron stars. (See "Gamma-Ray Telescope Finds First 'Invisible' Pulsar.")

The newfound bubbles, meanwhile, are made of hot, charged gas that's releasing the same amount of energy as a hundred thousand exploding stars.

"So you have to ask, where could energy like that come from" in the Milky Way? Finkbeiner said.

Gamma-Ray Bubbles Signs of Milky Way Feeding?

One possible answer is that the gamma-ray bubbles are evidence of an ancient burst of star formation at the center of the galaxy. If a huge cluster of massive stars formed millions of years ago, the giants could now be dying together, creating an outbreak of supernovae.

In that case, the bubbles could represent "the accumulated energy over many millions of years," Finkbeiner said.

"Another hypothesis, which is perhaps even more dramatic, is that the [mostly dormant] black hole at the center of the galaxy is active for a little bit," he said.

Scientists know that a supermassive black hole resides at the center of our galaxy, and it didn't get so big by sitting quietly. Instead, the black hole must go through stages when it gobbles up massive amounts of material.

When galactic black holes are actively feeding, they tend to spew high-energy jets from their poles. Astronomers have found such active galactic nuclei elsewhere in the universe, but have never before seen any convincing proof of this process happening in the Milky Way. (See "Black Holes Belch Universe's Most Energetic Particles.")

"So [the gamma-ray bubbles] might be the first evidence for a major outburst from the black hole at the center of the galaxy," Finkbeiner said.

The study team says that they have ruled out another theory that the bubbles could be proof of the mysterious substance known as dark matter.

According to theory, dark matter particles annihilate when they collide, releasing showers of new particles along with huge amounts of energy. It's thought that dense clumps of dark matter exist at the cores of galaxies, so looking for the results of collisions is one way astronomers hope to prove the substance exists.

"What bothers me about that explanation is those sharp edges that we see on the bubbles," Finkbeiner said, referring to the fact that the structures are well-defined domes.

Dark matter would have existed at the galaxy's core from the start, and the particles would have been continuously interacting.

"If something has been going on for billions of years and it is in a steady state, I would not expect to see a sharp-edged structure like this," Finkbeiner said.

Fermi Helps Pierce Gamma-Ray Fog

Finkbeiner and his team found the gamma-ray bubbles using data from Fermi's Large Area Telescope, the most sensitive gamma-ray detector yet launched.

The scientists then had to process the raw data so they could see through the "fog" of gamma rays that's made as high-energy electrons moving near the speed of light interact with light and interstellar gas in the Milky Way.

(Related: "Mysterious 'Dragons' Make Universe's Gamma Ray Fog.")

Further studies will be required to get at the true nature of the energy source blowing the bubbles, Princeton's Spergel said.

"But it is a striking image," he said, "and I think one that will be challenging astronomers over the coming years to do both future observational work and theoretical work to understand what's going on here and to make connections to other areas of galactic and extragalactic astronomy."